Invisible UX

The Future or Just Another Hype Cycle?

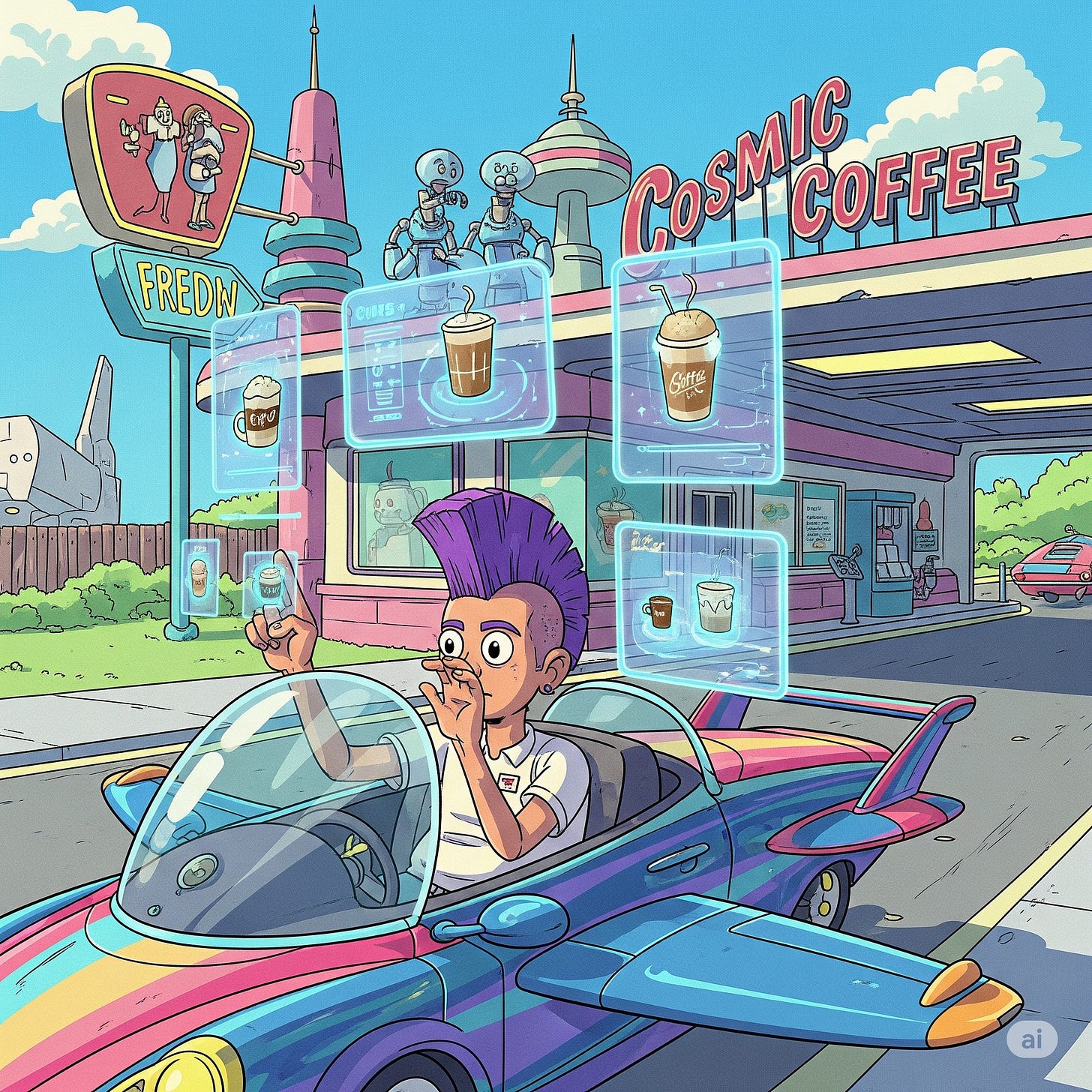

Felix Haas, a designer at Lovable, recently shared a perspective that’s been echoing through design circles: “Invisible UX is coming—and it’s going to change how we design products forever.” His post outlined a vision for a future where interaction dissolves, and experience is driven by intention, not interface.

It’s a compelling idea, and it raises a bigger question: Are we really heading toward a future where UX is invisible?

Let’s explore both sides of this shift.

Why Invisible UX Is the Future

Felix makes a strong case that AI is reshaping how we interact with digital products. And he’s right—many of our most powerful tools are already shifting toward intent-first interaction models.

Spotify, Google Assistant, Midjourney, and ChatGPT have all trained us to expect output without navigating complex interfaces. You type or speak, and it just happens. There are limited interactions that one has to go throuhg in order to find an answer.

This approach collapses friction. Instead of a user clicking five times to get what they want, they articulate a need and receive a solution. From a UX lens, it’s elegant. It prioritizes outcome over process.

In this future, the designer’s role becomes less about screens and more about understanding how humans express intent, and how systems interpret it. Designers will work with prompt architecture, user mental models, and trust signals rather than layouts and buttons.

Invisible UX reframes the job:

Less “where do we place this button?”

More “how do we make the outcome feel seamless, trustworthy, and human?”

If we’re designing experiences, not interfaces, then yes—Invisible UX is already here.

Why Invisible UX Is Overstated

But let’s be real for a moment.

“Invisible UX” sounds great on paper—but it glosses over some key realities:

Interfaces aren’t going anywhere.

Not everyone wants to talk to an AI. Many people still prefer visual options. Interfaces give users a sense of control, and they allow exploration without needing to know exactly what to ask for.Language is imprecise.

Saying “book me a cabin near Oslo” introduces ambiguity. What counts as “near”? What kind of cabin? What’s the trade-off between price and amenities? Interfaces let users see and decide. Invisible UX assumes users know what they want and can phrase it well—which isn’t always true.It’s not scalable for every product.

Invisible UX might work well for music, travel, or simple productivity tools. But what about complex enterprise systems, data dashboards, or design tools? These require structured, visual interaction. No one wants to “prompt” their way through a Figma file.Design still matters—visibly.

Even with AI agents, there’s a need to communicate state, affordance, and system status. A completely invisible interface can make users feel lost or out of control. That’s a UX failure, not a win.

The Middle Path: Designing for Intent and Interface

The real opportunity lies in hybrid UX.

We’re not replacing UI with prompts—we’re expanding the toolkit. The best AI products will still show you what’s possible, but let you shortcut the process with language when needed.

Designers won’t just be screen-makers—but we also won’t abandon visual design. We’ll layer interaction models:

Visual layouts for clarity

Conversational input for speed

Intelligent systems for prediction and adaptation

Invisible UX may not replace traditional design, but it challenges us to go deeper. It pushes us to design for human intent, ambiguity, and trust in new ways.

And that’s a good thing.

Final Thought

Whether or not the UI disappears, one thing is certain: The designer’s role is evolving. We’re being asked to craft not just layouts, but systems that think, respond, and feel intuitive across modalities.

The future of UX won’t be invisible. But it will be smarter, more flexible, and more human.

And we’ll be the ones designing it.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to the newsletter for more stories like this—insights, ideas, and the evolving world of tech and design through a UX lens.